Listen Up: It's Time to Rename the Smartphone

Smartphones are neither smart nor phones. Discuss.

Credit:

Credit:

Products are chosen independently by our editors. Purchases made through our links may earn us a commission.

Last year, former presidential candidate and renegade futurist Newt Gingrich posted a three-minute video imploring viewers to help him come up with a name for his "handheld computer." He was tired, he said, of the term "cell phone," and wanted to find a name that more accurately reflects the "change that has taken place" in telephony technology.

The problem was, he never once acknowledged the existence of the word "smartphone."

The internet had a lot of fun piling on Newt because, well, he’s Newt—and because it was a classic bit of bizarre, out-of-touch, what-the-heck-was-he-thinking comedy. But I think Newt’s flub also distracted us from an opportunity to start a real, meaningful dialogue about the term "smartphone"—specifically, why it’s stupid and how to get rid of it.

"Smartphone" is a clunky, misleading, redundant, and outdated word that has inexplicably become a cultural touchstone. I don’t expect it to go away any time soon, but it’s certainly worth starting a debate.

Here’s the simple fact that Newt was (unsuccessfully) trying to get across: Our mobile devices are more than just phones. They’re computers, GPS devices, cameras, web browsers, and game consoles.

It makes just as much sense to call these things "phones" as it does to call them "computers" or "browsers." And with WiFi calling, FaceTime, Google Hangouts, Skype, and other alternative conversational technologies on the rise, what does it even mean to have a "phone call" these days?

Then there’s the use of the word "smart" as a prefix for any device that connects to the internet: It’s not just lazy—it’s redundant. And it’s established a precedent for the industry that becomes harder and harder to overcome with each new product launch.

In a world where everything is smart, nothing is smart.

In some ways, it’s a lot like a virus—a self-replicating, mindless organism that has infected the tech world. Today we have smart homes, smart cars (not to be confused with Smart cars), smart fridges, smart watches, smart glasses, smart grids, smart cities, smart TVs… and the list goes on.

Are you annoyed yet? I know I am.

How did we get here?

The term smartphone has been around in one form or another since the mid-1990s, when it was initially used to refer to a variety of high-tech PDAs and landline phones.

Teenagers raised on iPhones may be surprised that something similar to their favorite texting device existed way back in 1996, but the then-revolutionary Nokia 9000 Communicator featured email, text-based web browsing, a calendar, calculator, notebook, QWERTY keyboard, and even fax capabilities.

One could certainly have been forgiven for calling it a smart phone. After all, it was certainly a lot brighter than the rest of its class, so it was only natural to give it a convenient differentiating adjective.

"There is a force in language change that I call 'laziness,'" jokes Meaghan Fowlie, a linguistics graduate at UCLA. "We tend to choose ways of saying things that are easier."

But the term actually goes back even further, to 1995, when it was used to refer to an AT&T device that combined the functions of a telephone and desktop computer. While the gadget was intended for landline communications, its internet connectivity was a first, effectively creating a new category of device.

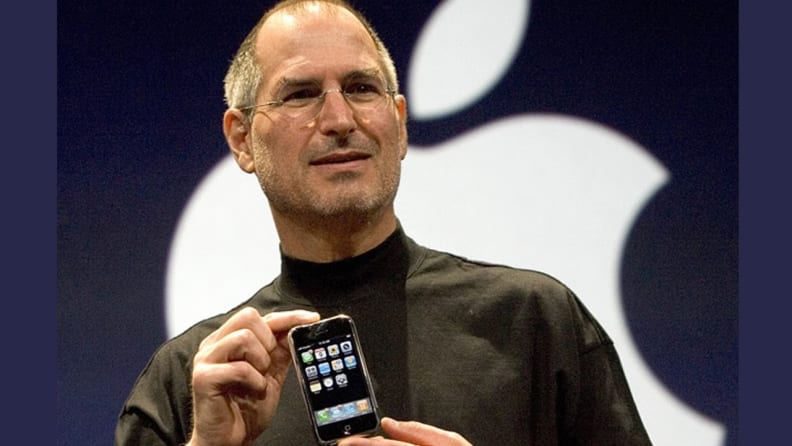

Steve Jobs unveils the iPhone at Macworld 2007.

But the term "smartphone" truly came to prominence with the release of the Apple iPhone in 2007. It was a game-changing, mass-market device that became a cultural phenomenon. It needed a game-changing definition—something consumers could use to say, "Yeah, but mine does this!"

But when Steve Jobs unveiled the iPhone all those years ago, he didn’t even use the word. Some in the media even tried to distance it from the existing smartphone concept, arguing that it was an entirely new kind of device.

So how did the term become so common?

As it turns out, the concept of the smart gadget actually predates that of the smart phone.

In the mid-1980s, the National Association of Home Builders began demonstrating the possibilities of automated "smart houses." A 1986 article from the Chicago Tribune predicted that, by the 1990s, families would remotely command their homes "to start the coffee, finish the laundry and make the dinner."

"Commuters will be able to turn off the air conditioner or turn on the security system by telephone from miles away," the report continues.

A lot of ideas for "smart" technology came out of the 1980s. Just take KITT here.

Certain words have a way of propagating through language. It’s a phenomenon known as memetics, wherein words or "cultural units" can function a lot like biological genes. Sometimes, undesirable traits find their way into a system and behave more like viruses than genes.

That first use of the word "smart" to describe a connected home likely encouraged other manufacturers and marketers to use the term to describe any innovation that improved upon an existing device, specifically with regards to connectivity. And it’s been proliferating ever since—just like a virus.

What’s so bad about "smartphone?"

Some viruses are asymptomatic. They can live inside a host for years, decades, or an entire lifetime without manifesting external symptoms. Others behave more insidiously.

The prefix "smart" is an insidious linguistic virus. As long as we don’t move to inoculate ourselves, we’ll be stuck with a system of lazy, nonsensical descriptors for any device that connects to the internet.

Of course, there’s a good chance we can just wait until feature phones and landlines completely disappear, and the use of "smart" will disappear along with them.

"One way that words are lost from a language is if no one ever has a reason to use them," says Fowlie. "This could happen with 'smartphone' if all phones become 'smart,' so we never have cause to say 'smartphone.'"

But that just leaves us with "phone," which is still totally inadequate.

According to data from Nielsen, use of text messaging outstripped use of phone calls in the U.S. as early as 2008. Similarly, the number of people who use their mobile devices to take pictures, access the internet, and record video has skyrocketed in recent years. According to a Pew Research study, 82 percent of smartphone owners use their device to take pictures, while some 80 percent use it to text.

A separate report released last year by Experian found the typical American spends roughly 58 minutes a day on their smartphone. Actually talking on the phone consumes a mere 26 percent of that time, while internet-related activities account for 39 percent.

In Europe, a survey found that web browsing, social networking, game playing, and music listening have all outstripped voice calls. Still, we never refer to our phone as our browser, stereo, camera, or gaming device.

Why? Because they do more than that. And that’s exactly why it’s not so smart to call them "phones."

So what should we call these things?

Okay, I’ll stick my neck out here: I think we should call them "mobiles."

It’s an umbrella term that highlights their most distinguishing feature—their portability. And as the differences between tablets, laptops, and phones continue to blur, "mobile" will be able to cover them all. It’s also a breezy two syllables, and it’s already in use in much of the U.K.

Sure, the term has its downsides: For one thing, it's an adjective, not a noun (but so is "wearable"). For another, it's really just an abbreviation of "mobile phone." I guess you could say I'm a descriptive grammar kind of guy.

But I’m hardly the first to offer an alternative. Former New York Times tech columnist David Pogue similarly opined in his 2009 review of the original Motorola Droid that "smartphone" is far too limited a term for our do-everything devices:

"A smartphone is a cellphone with e-mail—an old BlackBerry, a Blackjack, maybe a Treo. This new category—somewhere between cellphones and laptops, or even beyond them—deserves a name of its own."

Short of ideas himself, Pogue reached out to Twitter for guidance. The best suggestion he got was apparently "app phone," which—well, we’ve already covered why "phone" is the wrong path to take.

Writing for Gizmodo back in 2008—just a year after the first iPhone debuted—Jason Chen suggested we use "com." Here’s his rationale:

"Why com? I admit, the word may bring to mind web addresses, military jargon or even sci-fi, but it makes a lot of sense here. It's simple—like 'phone' which was colloquially adapted because 'telephone' was two syllables too long—and it's short for both 'communicator' and 'computer,' both of which describe the device in my pocket better than 'phone' does."

But here we are in 2014, half a decade down the road, and everyone is still calling them smartphones. Frankly, I don’t think any of these alternatives has a snowball’s chance in heck of catching on. Language—and particularly memetic language—is a stubborn thing.

Retailers are just as confused as we are about what to call these things.

Still, fate could throw us a curveball.

"It's very hard to predict how language will change," explains Fowlie. "Sometimes words become trendy and then fade away, like ‘groovy,’ and other times they become trendy and stay, like 'cool.'"

Regardless of what we eventually decide to call these things, one thing's for sure: The word "smartphone" is just not cool.