Don't Ignore Your Oven Dial, Just Take It with a Grain of Salt

New ovens offer more precision than ever before—why change a good thing?

Credit:

Credit:

Products are chosen independently by our editors. Purchases made through our links may earn us a commission.

In the recent article for Slate ("Ignore Your Oven Dial"), Brian Palmer advocates for a return to descriptive nomenclature of temperature—slow, moderate, and hot—and vigilant cooking in lieu of blindly trusting one's appliances.

We enjoyed the spirit of the article and agreed with some of its finer points, but we'd like to complement those points with some scientific data gathered from our growing database of lab-tested ovens.

Non-numerical temperature measurements worked in the past, in conjunction with closely monitoring food as it cooked. But the argument for verbal re-simplification is not as cut-and-dry as it once may have been. Since the invention of the oven thermostat in 1915, temperature control has improved considerably, and continues to improve.

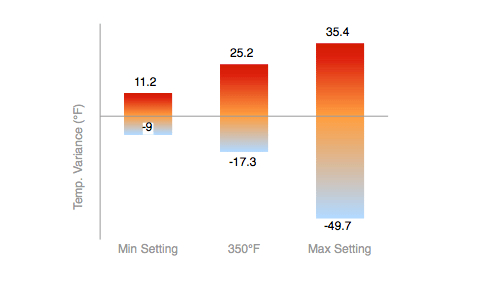

According to our data, which is gathered by 10 to 15 sensors inside each oven that we test, taking readings every 5 seconds, most ovens fluctuate by ±20°F throughout a cooking cycle, a 40° range total, or about ±6% at 350°F—consistent with the figures in the Slate article.

But the story doesn't end there. Standard on many new ovens, the convection fan’s innovation and increasingly common use has created a sort of paradigm shift. By moving the oven’s hot air, the convection fan delivers even temperatures and better heat transfer to food, saving time and energy. Besides limiting oven hot spots, many convection ovens perform exceptionally well in our variance tests, demonstrating incredible abilities to regulate temperature over time.

For example, a Samsung oven we just tested (around $1,300) exhibited a range of 11°F instead of the typical range of 40°F—that's closer to ±1.5%. Innovation is not dead in home appliances.

Sure, even the best ovens aren't totally precise, and the slow-moderate-hot system probably works fine for most recipes, which usually cook at standard temperatures like 350°F or 425°F. But when we have actual numbers to work with, it's silly to use vague, verbal stand-ins. In the J.L. Borges short story “Funes the Memorious,” an alternative counting system is conceived where numbers are assigned their own unique name instead of their base-ten value. The verbal substitutes turn out to be useless. How much hotter is slow than moderate? Why bother with words when numbers are more effective?

Then there are recipes that actually benefit from the typical ±6% (or better) precision. Cooking is chemistry, and efficient culinary reactions often require specific temperatures. Cakes can look nice and crisp on the outside, but will stay soggy on the inside. The same goes for roasts. Bread proofing, which makes bread rise before cooking, needs to be right around 100°F. If the temperature varies too much, the yeast dies, and you're left with a flat, dense loaf.

Many bakers can even tell whether refrigerated or room-temperature butter was used in a certain batch; temperature precision is important to them, to say the least. As temperature control improves in the future, chefs could take advantage of the even, accurate heat to develop cuisine that was once impossible to create.

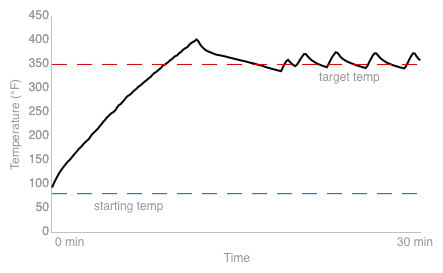

The Slate article also took issue with preheating, calling it “plain terrible advice.” We disagree. When an oven hits 130°F, it begins to cook the edges of its contents, but not the center. According to our tests, it takes an average oven about 10 minutes to hit 350°F (right in line with conventional wisdom, for what it's worth), so there's a significant time period where the oven cooks only the edges. It might look done on the outside, but the inside might still be raw.

Cooking a frozen pizza without preheating can be a disaster, too. If you're really unlucky, the pizza will thaw quickly without cooking, and parts of it can slip through the grate onto the heating elements below. Burnt cheese is not easy to clean. Talk about a hot mess. Some chefs also say that dishes like cookies can melt before they cook, effectively ruining the batch.

We also commonly see a phenomenon in our preheating and temperature variance tests (see image above), where ovens overshoot the target temperature significantly (albeit briefly) before settling into a rhythm of allowable fluctuation. For sensitive recipes, the extra heat can cause problems.

Luckily, there's a simple way to avoid these problems: Follow tradition, plan 10 or 12 minutes ahead, and just preheat the oven.

The necessity of exactness is ultimately up to individual users. Surely many people experience diminishing returns for a new or expensive oven, as various features, precision, and accuracy might not be used or required. While we heartily agree with the suggestion to always monitor food and not blindly trust your oven, we think it's silly to totally ignore your dial—just take it with a grain of salt. We hope that we have fully baked the matter.