Most people start out with a “Nifty Fifty” (50mm f/1.8) lens, because they’re cheap and strong performers. Even the more expensive f/1.4 version of these lenses are usually less than $500.

But what if you want something a little wider? A 35mm f/1.8 or f/2 lens will run you about $200, so an f/1.4 lens can’t be much more, right? Unfortunately, that’s not quite how it works. As focal lengths get lower, wide-aperture lenses get harder and harder to design—especially if you want to keep distortions and aberrations under control. The result is lenses like the $1,799.95 Nikon AF-S 35mm f/1.4G.

Why is it so expensive? Well, the precision of the design, the quality control, the fit and finish, and the "pro premium" all likely factor in. But in and out of the lab, this lens proved itself to be one of the sharpest primes that we’ve ever tested. It also offers excellent bokeh, a versatile fixed focal length, and a compact design.

But is it worth the price? Probably not.

Who's It For?

Like other 35mm prime lenses, the Nikon 35mm f/1.4G is a good choice for an all-around prime—an alternative to your kit lens or a heavy constant-aperture zoom for those times when you want flexibility and performance without the bulk. Sure, a 35mm prime isn't as flexible as either of those options, but it's about as flexible as primes get: wide enough for landscapes, tight enough for impromptu "environmental" portraits and street photography. It's basically either this or a 50mm prime if you're looking for a good full-frame all-rounder.

Like other pro-oriented lenses, the 35mm f/1.4G has a built-in focus scale.

But this lens isn't just about the 35mm focal length. It's also about the stellar low-light performance and shallow depth of field you get from the f/1.4 maximum aperture. Then there's the absolutely ridiculous edge-to-edge sharpness. Nikon also makes a 35mm f/1.8G that costs just $600. It's sharp, lightweight, and has solid bokeh of its own. But the 35mm f/1.4G blows it out of the water in virtually every metric.

Given the price point, though, this lens will really only appeal to professionals and hobbyists with big budgets. For most full-frame shooters, the Nikon AF-S 35mm f/1.8G ED is more than enough lens at less than half the cost. And if you want to spend even less money, the film-era Nikon 35mm f/2D is still in production (somehow), and offers excellent performance for $390. Just keep in mind that it won't autofocus on Nikon's entry-level DSLRs.

Look and Feel

Despite its hefty price tag, this hardly feels like a $1,800 lens. It’s solidly-built, to be sure, but it’s primarily made of plastic, lacks an aperture ring, and looks just like the far cheaper 35mm f/1.8G and 50mm f/1.4G lenses. In short, it looks like a Nikon G-series lens, which it is. For better or worse, Nikon has stuck to a universal look and feel for its digital-era lenses (with a couple notable exceptions), and this is the new normal.

Despite its super-wide f/1.4 aperture, the lens has a relatively conservative 67mm filter diameter.

Shooting with the 35mm f/1.4G is as simple as it gets. The onboard SWM autofocus motor is compatible with all Nikon DSLRs; it's quick, quiet, and smooth, even when shooting video. The lens body has few physical controls—essentially just a focus mode switch and a massive focus ring. Like other G-series lenses, focus is by wire. There are no hard stops to let you know when you've hit the end of the focus range, but there's a little click before the ring keeps spinning.

One of Nikon's most useful G-series additions is the M/A focusing mode, which lets you override the AF for small adjustments.

This G version is Nikon's first autofocus 35mm f/1.4. The only previous version was the 35mm f/1.4 Ai-s manual focus lens, which was a stellar performer for its era and had an immaculate all metal build. Aside from its construction and size, however, the modern 35mm f/1.4G is superior in every respect: sharper, with better bokeh, and boasting extremely accurate autofocus.

Image Quality

The Nikkor AF-S 35mm f/1.4G is capable of capturing some truly wonderful images. In our lab tests, it proved itself to be one of Nikon's sharpest primes, with minimal distortion, no noticeable chromatic aberration, and true corner-to-corner sharpness through almost the entire aperture range.

EXIF: 35mm, ISO 100, 1/160, f/1.4

We're used to seeing exceptionally sharp results from the Nikon D810 thanks to its 36.3-megapixel sensor, but this lens exceeded even that high standard. In our sharpness test, we use a unit of measurement called "line widths per picture height" at MTF50, where anything over 2,000 is generally considered excellent.

The Nikkor 35mm f/1.4 didn't just crest 2,000 in the center at every single aperture, it averaged over 2,300 lines across the entire frame from f/2.8 to f/8, with the center nearly crossing 3,000 lines at f/4 and f/5.6. While this isn't quite as sharp as the best lenses we've ever tested—the Sigma 50mm f/1.4 DG HSM Art is a bit sharper—it's certainly in the upper echelons.

EXIF: 35mm, ISO 100, 1/400, f/2.8

Out in the field, the lens continued to outdo itself. The wide-normal field of view makes this an almost ideal walkaround lens, with generally superb (if occasionally a little busy) bokeh and a field of view that produced images with a distinct character. It's a potent combination, making this an excellent choice for pretty much any photographer save for sports and wildlife shooters who can't get close enough to the action.

EXIF: 35mm, ISO 100, 1/2000, f/1.4

Below you can see sample photos taken with the AF-S Nikkor 35mm f/1.4G mounted on a Nikon D810. Click the link below each photo to download the full-resolution image.

Testing: Overall

When evaluating any lens, we focus on four key areas: sharpness, distortion, chromatic aberration, and bokeh. A perfect lens would render the finest details accurately, wouldn’t distort straight lines or produce ugly fringing around high-contrast subjects, and would create smooth out-of-focus areas.

With such a high price tag, the Nikon 35mm f/1.4G (just like the rival Canon EF 35mm f/1.4) has to put in a stellar performance to justify the expense. In our lab tests, it didn't disappoint. Paired with the Nikon D810, it delivered razor-sharp results in the image center right from f/1.4, continuing to excel all the way through to f/16. With minimal distortion, a moderately wide angle of view, and killer bokeh, this is a lens that's worth the investment—if you can afford it or need it for professional reasons.

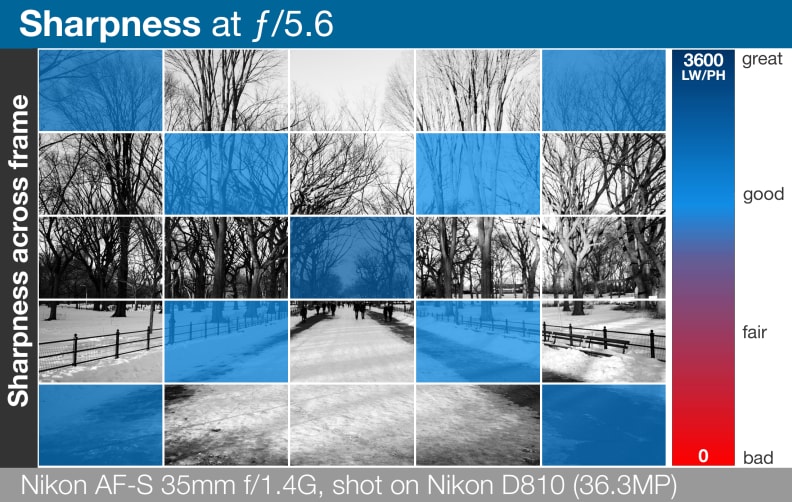

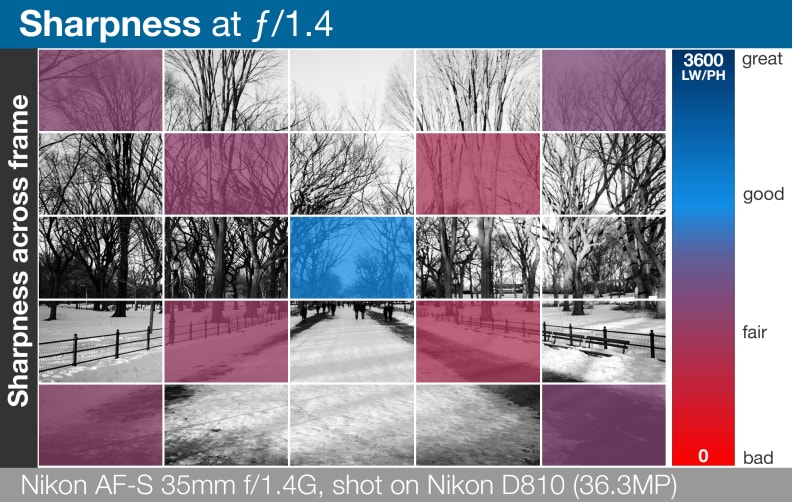

Testing: Sharpness

A lens's sharpness is its ability to render the finest details in photographs. In testing a lens, we consider sharpness across the entire frame, from the center of your images out to the extreme corners, using an average that gives extra weight to center performance. We quantify sharpness using line widths per picture height (LW/PH) at a contrast of MTF50.

This lens is best when stopped down to f/5.6.

We tested the Nikon 35mm f/1.4G with the Nikon D810, which packs a 36-megapixel sensor that's the ideal platform to see just what the lens is capable of. In the center of the frame, it starts strong with a result of over 2,225 lines. By f/2, it's already over 2,550 lines, and it tops out at 2,900 lines from f/4 to f/5.6.

Moving away from the center, the results dip slightly, but it's still a strong performance compared to similar lenses. In the midway region (50% from the center) the 35mm f/1.4G only manages around 1,100 lines at f/1.4 and f/2, but this quickly jumps up to 1,950 lines at f/2.8 before peaking at 2,290 lines from f/5.6 to f/8.

Center sharpness is decent, but everything else suffers at full wide.

In the corners of the frame, results are actually slightly better than the midway regions—a sign of significant (and expensive) optical correction by the lens designers. Resolution there starts at 1,370 lines at f/1.4, improves to 2,050 lines by f/2.8, and crests at 2,650 lines at f/8. Overall, it's an extremely impressive result—especially for a wide-to-normal prime lens.

Testing: Distortion

We penalize lenses for distortion when they bend or warp images, causing normally straight lines to curve.

There are two primary types of distortion: When the center of the frame seems to bulge outward toward you, that’s barrel distortion. It's typically a result of the challenges inherent in designing wide-angle lenses. When the center of the image looks like it's being sucked in, that’s pincushion distortion. Pincushion is more common in telephoto lenses. A third, less common variety (mustache distortion) produces wavy lines.

The Nikon 35mm f/1.4G provides a slightly wider than "normal" angle of view, encompassing a little more than the human eye typically sees. Usually, lenses in this range suffer from slight barrel distortion (it tends to get more intense the wider you go), and this one is no exception. Still, it does a better job of keeping lines straight than some competitors.

In our test shots, we recorded about 1.2% barrel distortion. It's a consistent, minor curve that's easy enough to correct in your photo editing suite of choice, though it will be noticeable in some shots straight out of the camera.

Testing: Chromatic Aberration

Chromatic aberration refers to the various types of “fringing” that can appear around high contrast subjects in photos—like leaves set against a bright sky. The fringing is usually either green, blue, or magenta and while it’s relatively easy to remove the offensive color with software, it can also degrade image sharpness.

The wider a lens's aperture, the more vulnerable it tends to be to aberrations. The Nikon 35mm f/1.4 has a very wide aperture indeed, but it outpaced our expectations in this regard with only minor issues from f/1.4 to f/2.8. CA all but disappears between f/4 and f/16, where it suddenly reappears. But even at its worst, the 35mm f/1.4G's CA is minor and easily correctable in post-production.

Testing: Bokeh

Bokeh refers to the quality of the out of focus areas in a photo. It's important for a lens to render your subject with sharp details, but it's just as important that the background not distract from the focus of your shot.

While some lenses have bokeh that's prized for its unique characteristics, most simply aim to produce extremely smooth backgrounds. In particular, photographers prize lenses that can produce bokeh with circular highlights that are free of aspherical distortion (or “coma”).

Though bokeh isn't as crucial for wide-angle and normal primes as it is for portrait and wildlife lenses, the 35mm f/1.4G stands to benefit from smooth out-of-focus areas since can be used for off-the-cuff portraiture. Thankfully, it offers above-average performance for a lens of its type.

The bokeh you get is slightly busier than what you'd get from Nikon's 50mm f/1.4, it's still quite good overall. The biggest issue you'll encounter is inconsistency in the out-of-focus areas, which exhibit some minor haloing or "ni-sen" bokeh, especially with background points of light at f/1.4.

Conclusion

If you were only aware of first-party lenses from Canon and Nikon, you’d be forgiven for thinking that 35mm f/1.4 lenses are almost impossible to manufacture. Why else would they cost in excess of $1,600, when 35mm f/1.8 and f/2 lenses go for a third or less of the price?

But luckily there are plenty of third-party options to consider. Sigma’s extremely similar 35mm f/1.4 DG HSM Art is a stellar performer, albeit without weather sealing, and it costs $900. If you don't mind an even chintzier plastic build and focusing manually, the incredibly sharp Samyang 35mm f/1.4 is an absolute steal at a little over $400. If you're having a hard time justifying Nikon's $1,500-plus price point, well... so are we.

The 35mm f/1.4G balances well on Nikon's full-frame FX bodies, but it might be a bit front-heavy on cameras like the D3300.

But in truth, we’d have trouble justifying it even without these alternatives. It's just an awful lot of money to spend on a normal prime lens. IF you're a pro who will get a lot of use out of a general purpose lens like this? Sure, but your company will buy it or you can write it off. For hobbyists it's a pure luxury purchase, strictly for those with disposable income to burn.

Which isn’t to say that this lens isn’t good. It’s fantastic in virtually every respect. But for most people—even those who can afford it—the opportunity cost is just too high. Maybe you can justify spending $1,800 on this one lens, but can you justify buying it instead of three other, equally good lenses?

If that’s not an issue for you, then worry not; for the right buyer with money to burn, this is a great lens. For the rest of us, it’s a tall order.

Meet the tester

TJ is the former Director of Content Development at Reviewed. He is a Massachusetts native and has covered electronics, cameras, TVs, smartphones, parenting, and more for Reviewed. He is from the self-styled "Cranberry Capitol of the World," which is, in fact, a real thing.

Checking our work.

Our team is here to help you buy the best stuff and love what you own. Our writers, editors, and experts obsess over the products we cover to make sure you're confident and satisfied. Have a different opinion about something we recommend? Email us and we'll compare notes.

Shoot us an email