Credit:

Reviewed.com / Ben Keough

Credit:

Reviewed.com / Ben Keough

Products are chosen independently by our editors. Purchases made through our links may earn us a commission.

- What Is a Zoom Lens? If you like multitasking, you’ll love these lenses.

- Why Buy a Zoom Lens? Convenience, convenience, convenience.

- Types of Zoom Lenses There are zooms to fit every need.

1. What Is a Zoom Lens?

If you like multitasking, you’ll love these lenses.

Most consumer-oriented lenses on the market today are zooms. In contrast to prime lenses, which cover just a single focal length, zoom lenses cover a range of focal lengths. That gives them the edge in flexibility, making them ideal go-everywhere companions.

Some zooms only cover a wide-angle range, others focus on telephoto focal lengths, and still others try to do it all. Many are priced to attract new camera buyers—particularly those that come bundled with DSLRs and mirrorless cameras—but they’re available at virtually every price point. They can also vary greatly in terms of size, weight, and image quality.

Naturally, the best pro-grade zooms are big, heavy, and expensive. But they also offer notable advantages, like constant maximum apertures, superior build quality, and tough weather sealing.

{{ product_shelf title='Top-Rated Zoom Lenses', category="lenses", categories__slug="zoom", count="5"}}

2. Why Buy a Zoom Lens?

Convenience, convenience, convenience.

The best reason to buy zooms is for the convenience they provide. Though they might be consistently outclassed by prime lenses when it comes to sharpness and distortion control, it’s hard to beat zooms for handiness.

A good zoom can help make sure you get the shot, even with a fast-moving subject.

Flexibility: With a zoom lens, you can shift your perspective with a flick of your wrist—something you can't do with a prime lens. Superzooms, like the common 18-200mm or 28-300mm, let you shoot everything from wide-angle landscapes and architectural shots to portraits and wildlife photos without ever changing to another lens. More frequently, shooters will pair a normal zoom (like an 18-55mm or 28-70mm) with a telephoto zoom (like a 55-200mm or 70-300mm). With either of these setups, you’re covered for shooting virtually any subject.

Getting the Shot: Prime lenses have a lot of advantages, but if you’re shooting in an uncontrolled, unpredictable environment, they have one big down-side: it’s easy to get stuck with the wrong one on your camera. With a zoom lens, this is rarely an issue. Imagine you’re shooting a soccer game. If you’ve got the right zoom mounted on the camera, you can sit in the bleachers and get wide shots of the entire field without worrying you’ll miss your kid’s goal. With a wide-angle prime on the camera, you’d be out of luck.

Ease of Use: If you’ve recently upgraded from a point-and-shoot to a DSLR or mirrorless camera, a zoom will provide a more familiar user experience than a prime lens. Primes require you to get out of your comfort zone, to “zoom with your feet” and get creative with how you approach a scene. Zoom lenses, on the other hand, bring your subjects to you.

Portability: As a rule, zooms are larger and heavier than prime lenses. But with that said, you need several primes to cover the same range as a single zoom. If you’re happy with the image quality you get from a do-it-all zoom, it may actually save you weight and bulk over a prime lens setup.

3. Types of Zoom Lenses

There are zooms to fit every need.

What kind of zoom is right for you? Read on to find out.

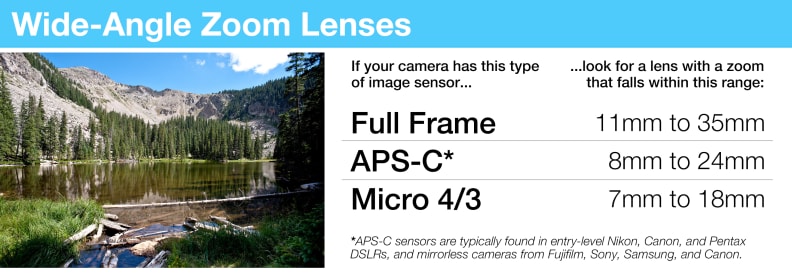

Wide-angle zooms are ideal for landscape and architectural shooting, since they’re able to capture a huge field of view in a single shot. Full-frame zooms like Sigma’s 12-24mm f/4-5.6 DG II HSM and Nikon’s pricier but spectacular 14-24mm f/2.8G are constant companions for event photographers. Similar lenses are also available for APS-C DSLRs and mirrorless cameras (like Sigma’s 8-16mm f/4.5-5.6) and Micro Four Thirds (like Panasonic’s 7-14mm f/4).

Fisheyes are another kind of wide-angle, albeit one you wouldn’t want to use for most architecture or landscape shots. Pentax, for example, makes a 10-17mm lens that produces fisheye shots at 10mm and more standard wide-angle photos at 17mm.

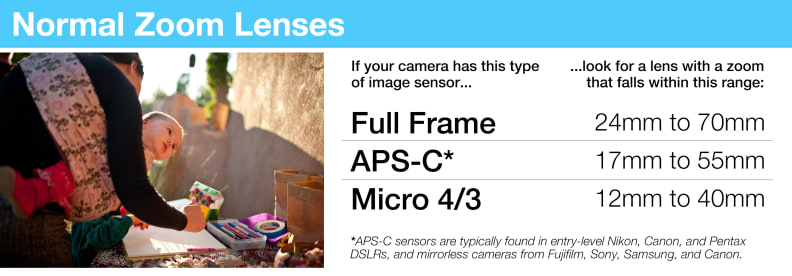

Normal zooms are bread and butter lenses for amateurs and professionals alike. The 18-55mm kit lens that probably came with your DSLR is one example; Canon’s spectacular 24-70mm f/2.8L II (a $1,800 professional lens) is another. Pricing and image quality can vary widely, but these zooms all provide the same basic functionality—a convenient zoom range that goes from wide-angle to short portrait. This makes them ideal for all-day shooting when you don't need the extra reach of a superzoom.

More expensive models like the aforementioned Canon (and its Nikon equivalent) are sharper and offer wider maximum apertures that can boost low-light results and provide better bokeh. But those improvements come at the expense of weight and bulk.

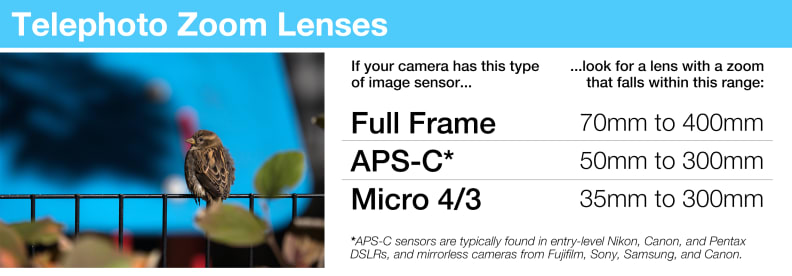

A good telephoto zoom is the perfect complement to a normal zoom—in fact, there’s a good chance your DSLR or mirrorless camera came bundled with both. If not, a 55-200mm or 55-300mm lens that picks up where your 18-55mm leaves off is a smart, cost-effective way to round out your system. These lenses bring your subject close, making them great for sports and wildlife shooting.

Just as with normal lenses, there are high-end pro versions—most of the major first- and third-party brands make full-frame 70-200mm f/2.8 options, and some third-parties make APS-C specific 50-135mm or 50-150mm f/2.8 lenses. For its part, the Micro Four Thirds system has two compelling high-end telephoto zooms in the Panasonic 35-100mm f/2.8 and Olympus 40-150mm f/2.8.

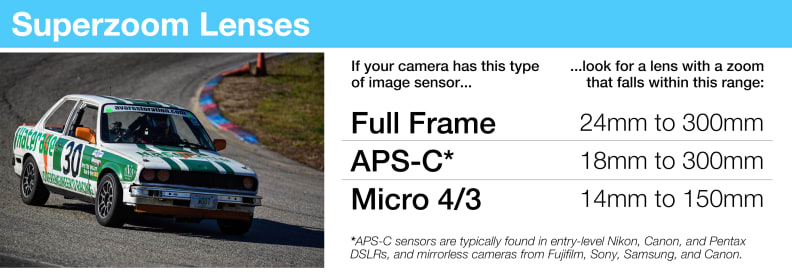

Superzooms are a staple of the point-and-shoot camera market, so it’s only natural that they’re popular with users upgrading to their first DSLR or mirrorless camera. These lenses start at around 18mm and go all the way out to 200mm or 300mm, covering virtually every conceivable perspective you could want. Sounds great, so what’s the catch?

Well, just like the point-and-shoots they mimic, these lenses make big image quality tradeoffs in exchange for their huge reach. There’s more image distortion (straight lines end up curved), there are more aberrations (distracting colored fringing around high-contrast subjects), and the results tend to be a lot less sharp than what you’d get from more modest optical designs. For some, though, the convenience is well worth the tradeoff.